The first President of Botswana 1966 to 1980.

Celebrating Diversity at the Bar

- Introduction

- Diversity Timeline

- Edward Akufo-Addo

- Obafemi Awolowo

- Joyce Bamford-Addo

- Solomon Brandaranaike

- Charlotte Boaitey-Kwarteng

- Joseph Ephraim Casely Hayford

- Eugenia Charles

- S Chelvan

- Thomas Morris Chester

- Learie Constantine

- Edward Cragg Haynes

- Patricia Dangor

- Coomee Rustom Dantra

- Gifty Edila

- Ezlynn Deraniyagala

- Taslim Olawale Elias

- Martin Forde

- Arthur Dion Hanna

- Ma Pwa Hmee

- Alexander Isbister

- Sibghatullah Kadri

- Seretse Kharma

- Moleleki Didwell Mokama

- Tunde Okewale

- Ashitey Ollennu

- Vallabhbhai Patel

- Lily Tie Ten Quee

- Ponnambalam Ramanathan

- Edward Richards

- Khushwant Singh

- Manjiit Singh Gill

- Teo Soon Kim

- Leslie Thomas

- Stella Thomas

- Leonard Woodley

Home › Celebrating Diversity at the Bar › Seretse Kharma

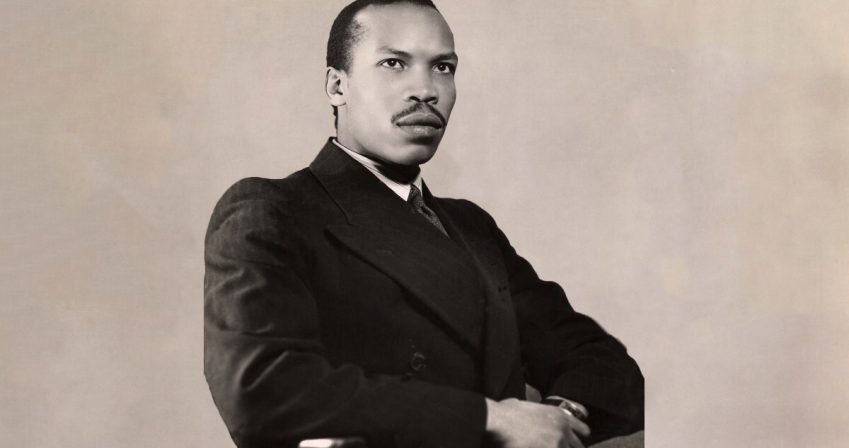

Sir Seretse Khama GCB KBE

1921 – 1980

Sir Seretse Khama was admitted to Inner Temple on 14 October 1946 and went on to become the first president of the independent Republic of Botswana in 1966. His marriage to a white Englishwoman in London in 1948 whilst he was studying at the Bar caused diplomatic tension in Africa and the UK and drew the attention of the public to the inequities of apartheid in South Africa, the rise of nationalism in Africa and black immigration in Britain in the 1940s.

Seretse was born on 1 July 1921 in Bechuanaland (now Botswana) and was the eldest son of Sekgoma, the Chief of the Bamangwato Tribe and ruler of the Bamangwato Reserve in the British Protectorate of Bechuanaland. His father died in 1925 when Seretse was four years old and Seretse became ruler under a regency led by his uncle. Seretse was educated in South Africa, being awarded a degree in law and administration in 1944. His uncle then arranged for him to continue his education at Balliol College at Oxford University, where he studied between 1944 and 1946.

When Seretse was unable to sit his exams (he was not proficient enough in Latin), he left Oxford University and was admitted to The Inner Temple in 1946 where he continued his legal studies. In taking this step he followed the path of many other leaders of early national independent leaders who trained at the Bar. In the first half of the twentieth century, English common law operated in the commonwealth countries and many wealthy and prominent families sent their sons to England to train to become barristers.

Sir Seretse Khama by Bassano Ltd Image Source: https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw61557/

Admission 1946, Inner Temple

However, at this point the plan for Seretse’s life and career changed dramatically. Whilst in London studying for his Bar examinations he met Ruth Williams through the London Missionary Society. She was a secretary working for a Lloyds underwriter in London. They began a relationship and married on 29 September 1948 in a civil wedding ceremony, the Bishop of London refusing to marry them without the permission of the British government. They also faced opposition from both their families.

This marriage of a Black African Chief to a white English girl caused a diplomatic storm in the British Commonwealth which was to last almost a decade. The couple moved to Bechuanaland in 1949 with the agreement of the tribal elders and the Bamangwato tribe declared him as chieftain in 1949. However, the British government was under pressure from the apartheid white governments in South Africa and Rhodesia who disproved of Seretse’s mixed marriage. The British government removed him as chieftain in 1950; the couple were exiled from Bechuanaland and returned to live in London. Seretse nominally continued with his legal studies and talked of starting a career as a barrister in Africa. However, he was never called to the Bar or practised law in England or Africa.

Between 1950 and 1955 there was a public outcry in Britain and America in support of the couple, whose story was portrayed as a dramatic film with star crossed lovers being thwarted by the government and their families. The publicity highlighted the apartheid regime in South Africa. Under increasing pressure from people within Britain, in 1956 the government allowed the couple to return to Bechuanaland on the condition that Seretse renounced his chieftainship.

On his return to Bechuanaland Seretse continued his involvement with politics and founded the Botswana Democratic Party in 1962. He negotiated Botswana’s independence and became the country’s first president in 1965. He was subsequently knighted in 1966 to recognise his efforts in the independence movement.

Seretse continued as president for four terms. During this time he established Botswana as a multi-racial democracy, bringing different ethnic groups together and successfully transferring power peacefully from traditional tribal chiefs to the newly established democratic government. He introduced universal education and presided over rapid economic growth, assisted by the discovery of diamond and other mineral deposits in the country. He remained president until his unexpected death from pancreatic cancer on 13 July 1980.

By Liz Hardie