The sixteenth century was an age of expansion for the common law and its practitioners, and all the inns were substantially enlarged and beautified during the Tudor period. Spenser was referring to the Temple when he wrote in Prothalamion (1596) of

Who We Are

- The Inner Temple Today

- Bench Table Orders

- Education and Qualification Rules

- Consultation Responses

- Time to Change

- We Are a Living Wage Employer

- Social Mobility Employer Index

- The Council of the Inns of Court

- Car Park Terms and Conditions

- Licensing

- Outreach Safeguarding Policy

- Applications Misconduct Policy

- 🔗 Searcys Anti-Slavery Policy

- Scholarships Feedback Policy

- Scholarships Deferrals Policy

- Modern Slavery and Human Trafficking Policy

- Environmental Policy

- Scholarships Appeals Policy

- Equality & Diversity

- PASS Travel, Accommodation and Subsistence Policy

- Anti-Bribery

- Complaints

- Privacy

- Conflicts of Interest

- Volunteer and Participant Code of Conduct

- Freedom of Information

- Admissions Database 1547-1940

- The Archives

- Bench Table Orders 1845-1945

- Calendars of Inner Temple Records 1505-1845

- The Christmas Accounts 1614-82

- The Freehold

- History of The Inner Temple Video

- In Brief

- Charles and Mary Lamb in the Inner Temple

- Grand Day

- Life in Halls: Designs of the Previous Incarnations of the Inner Temple Hall

- Gorboduc, or the Tragedy of Ferrex and Porrox

- Lord Robert Dudley, 'chief patron and defender' of the Inner Temple

- Lost in the Past : The Rediscovered Archives of Clifford's Inn

- Paintings

- Phoenix from the Ashes: The Post-War Reconstruction Of The Inner Temple

- Silver - Extract from 'A Community of Communities'

- The "Unfortunate Marriage" of Seretse Khama

- The admission of overseas students to the Inner Temple in the 19th century

- The Inns Of Court & Inns Of Chancery & their Records

- William Cowper of the Inner Temple

- William Niblett - A Life Re-Examined

- Library Manuscripts

- Paintings Collection

- Pegasus Emblem

- Silver Collection

- Our People

- Work for Us

- Notable Members

Home › Who We Are › History › The Inner Temple History › The Sixteenth Century

The Sixteenth Century

...Those bricky towers, the which on Thames broad aged back doth ride, wherein the studious lawyers have their bowers, And whilom wont the Templar knights to bide...

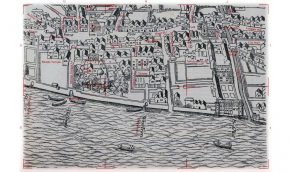

Map of Tudor London England’s Greatest city in 1520 published by the British Historic Towns Atlas and London Topographical Society

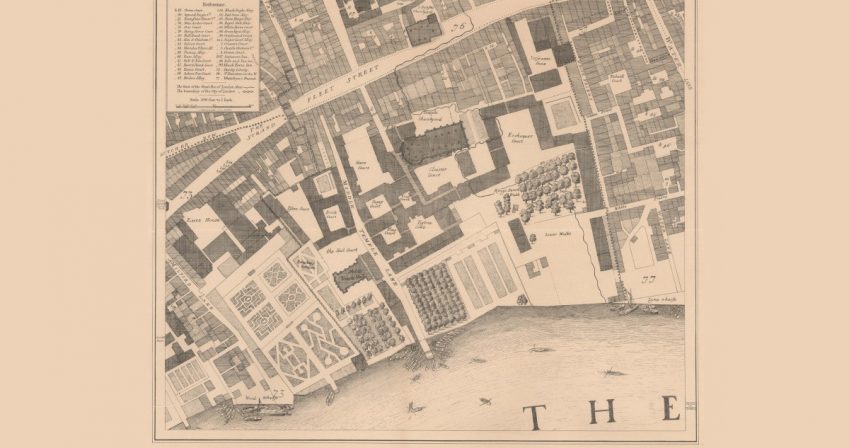

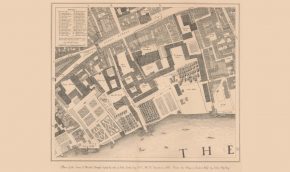

1671 Plan of Temple

The characteristic brick of the late Elizabethan Temple must have represented, for the most part, recent construction. Some of the development may be traced through the Inn’s records, since the minutes of parliament (the governing body of benchers) exist from 1505; but most building projects were carried out with private money, the investors retaining a freehold interest in the chambers. Very few of these Tudor buildings survived into the nineteenth century, though the name Hare Court still commemorates a rebuilding scheme financed by Nicholas Hare in 1567. In Hare’s time there were 100 sets of chambers in the Inn, making it the second largest (after Gray’s Inn); in 1574 it is recorded that only 15 benchers and 23 barristers lived in, well outnumbered by the 151 resident students. Celebrated alumni from this period included Sir Thomas Audley (d. 1544), the Inn’s first lord chancellor, two subsequent holders of the great seal (Sir Thomas Bromley and Sir Christopher Hatton), and, above all, Sir Edward Coke (d. 1634). Coke is still remembered for his Reports and Institutes, which included a Commentary on Littleton; but perhaps the greatest achievement of his stormy judicial career was the foundation of English administrative law.

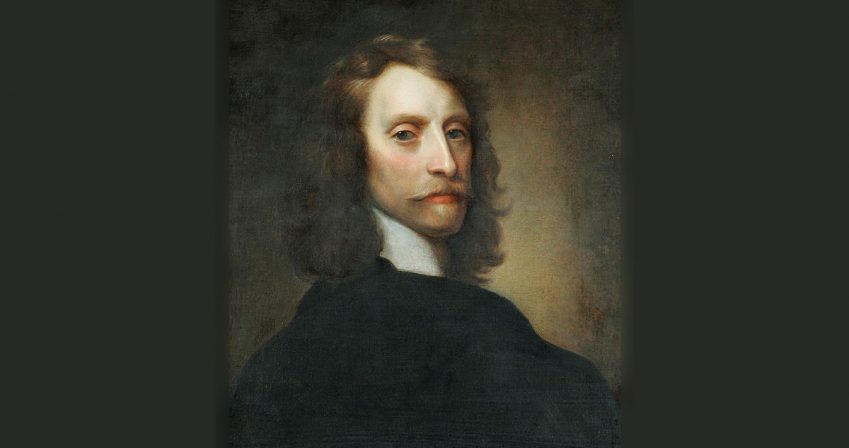

Sir Edward Coke 1552-1634 by Paul Van Somer. Image © The Inner Temple

Coke’s career leads us into the seventeenth century; although he left the society on becoming a serjeant in 1606, he was allowed to retain chambers in his beloved Inner Temple until his death and must have been a dominant presence. The expansion of membership continued throughout that period: over 1,700 students were admitted to the Inn between 1600 and 1640. In 1642, however, the news of Edgehill sent bench and bar rushing home. The Inns were all but closed for four years, and the legal university suffered a mortal collapse. Readings were discontinued, and their revival after the interregnum was short-lived. The first Restoration reading (by Sir Heneage Finch in 1661) was a magnificent occasion. King Charles II attended the reader’s feast in person, and the Duke of York (later King James II) became the first royal bencher. But readers in general found it was easier to pay the fine for default than to prepare lectures and pay for feasts, while the Inn doubtless concluded that monetary compensation was more useful than specific performance.

Readings therefore petered out in 1678. (The Inn has nevertheless continued to elect readers, this being the sole qualification for having one’s coat of arms erected in hall; in recent times the Reader has normally held office for the calendar year prior to becoming Treasurer.)

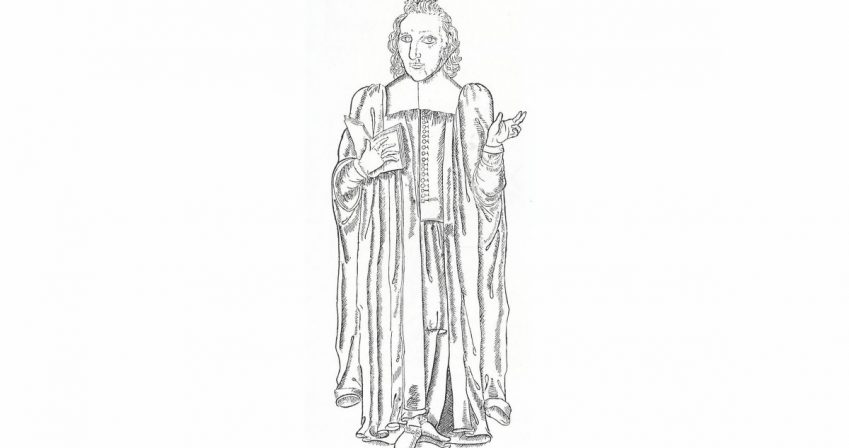

A reading in 1668. Brass (at Great Bookham, Surrey) of Robert Shiers, who died in office: the only known picture of a reader giving his lectures. Image © Professor Sir John Baker

In the Restoration period the Inn suffered three serious fires, affecting mainly the northern and eastern parts, and in consequence rebuilt Hare Court, Tanfield Court and King’s Bench Walk – now the oldest range of chambers still in use in the Inn. Distinguished alumni included John Hampden (d. 1643), opponent of ship-money, John Selden (d. 1654), legal historian and defender of English liberties, Henry Rolle (d. 1656) and Sir John Vaughan (d. 1674), two very learned chief justices, Lord Nottingham (d. 1682), the ‘father of modern equity’, and the notorious ‘Judge Jeffreys’ (later Lord Chancellor Jeffreys, d. 1689) of the Bloody Assizes.

The 1677 John Ogilby plan shows the outer limits of the fire of London

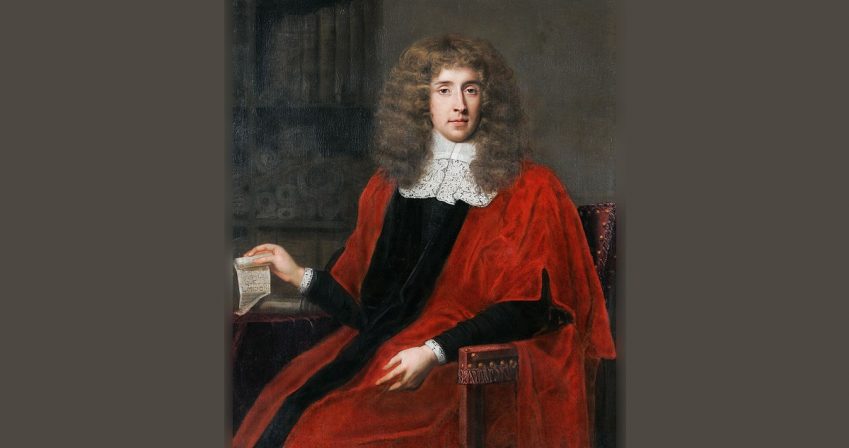

Portrait of John Selden (1584-1654) by Sir Anthony van Dyck. Image © The Inner Temple

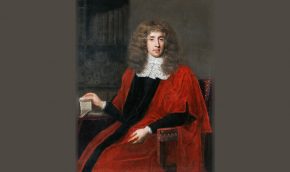

George Jeffreys, 1st Baron Jeffreys of Wem. Attributed to William Wolfgang Claret. Image © The Inner Temple